A Healthy Church Doesn’t Have Any Republicans or Democrats

Transcript

Rick Barry: How would you feel if you saw a white pastor get up at the end of church one week and pray, “Thank you, God, that you’ve made me a knowledge worker, not blue-collar. That you’ve made me white, not black. And that you’ve made me a Republican, not a Democrat?”

This is the first in a series of videos we’re going to make introducing the what, the why and the how of political diversity in the church.

The Cultural Divisions Of Jesus’ World

Galatians 4:4

Galatians 4:4 tells us that God sent Jesus into the world at just the right time. And the world Jesus was born into—the world of Israel, under Roman occupation, after the ascension of Caesar Augustus—was a world with three big cultural divides: Jews and gentiles. Free people and slaves (also called “bondservants”). And men and women.

The people of Israel divided the world into Jews and gentiles. (Colloquially, they called gentiles “Greeks.”) The Romans divided themselves and their subjects up between free people and slaves, or servants, and this had big implications for social status, upward mobility, and your general relationship to the state. And both Jewish society and Roman culture drew strong distinctions between men and women when it came to legal privileges, access to education, commercial activity, inheritance rights, and social credibility.

These were widely accepted divisions in the world that Jesus was born into, but Jesus dignified women as well as men throughout his ministry. He said he came to send his followers into all the earth, not just Israel. And he both healed slaves, who were nothing before Rome, and praised people like the faithful Centurion and Zacchaeus, who had Roman power and influence and authority.

Galatians 3:28

In Galatians 3:28, Paul—a man who was at once thoroughly Jewish and thoroughly fluent in Roman—sums this all up by telling his readers that there is no Jew or Greek, free or slave, man or woman. He says all are one in Christ Jesus. They have to learn together and grow together if they are going to live out the gospel.

For more information on the history of this "blessing of identity," see Yoel Kahn's The Three Blessings: Boundaries, Censorship, and Identity in Jewish Liturgy.

Now, there’s a little bit of debate about how that exact turn of phrase ended up in that letter: Some scholars say it’s wholly original. Paul came up with it. I haven’t read all of the literature, but I don’t think that that’s the majority view. Instead, some researchers and pastors say it’s a riff on a common Jewish prayer that academics sometimes refer to as a “blessing of identity.” But other historians say that that “blessing of identity” probably didn’t work its way into the rabbinical tradition until later. Instead, those historians say that Paul’s statement in Galatians 3:28 and that “blessing of identity” probably share a common, non-Jewish source, something that they’re both adapting or reacting to.

Cultural Diversity Is Essential For The Church

But no matter where you fall in that debate, the point Paul is making is still roughly the same: For the church to function properly, people who are told by their culture that they have nothing in common have to cling to one another and subject ourselves to one another. Willingly. More than willingly—joyfully! Mutually. And normally.

At the time, that meant devout Jews had to share a table with gentiles, who they considered to be immoral, idolatrous, oppressive and unclean. The elite, cosmopolitan Romans had to share a table with the Israelites, who they considered to be kinda backwater weirdos. Free people had to give up the pride of place they enjoyed over the second-class citizens.

For us, this means that if someone can go to a church and look around and explain what’s holding these people together besides the Holy Spirit, that church isn’t demonstrating the power of God the way they we’re called to.

This wasn’t easy for early Christians to do when it came to to the Jewish/Greek, free/slave and male/female divides, and it’s not easy to do when it comes to the kinds of things that fuel the liberal/conservative divide that we live with today.

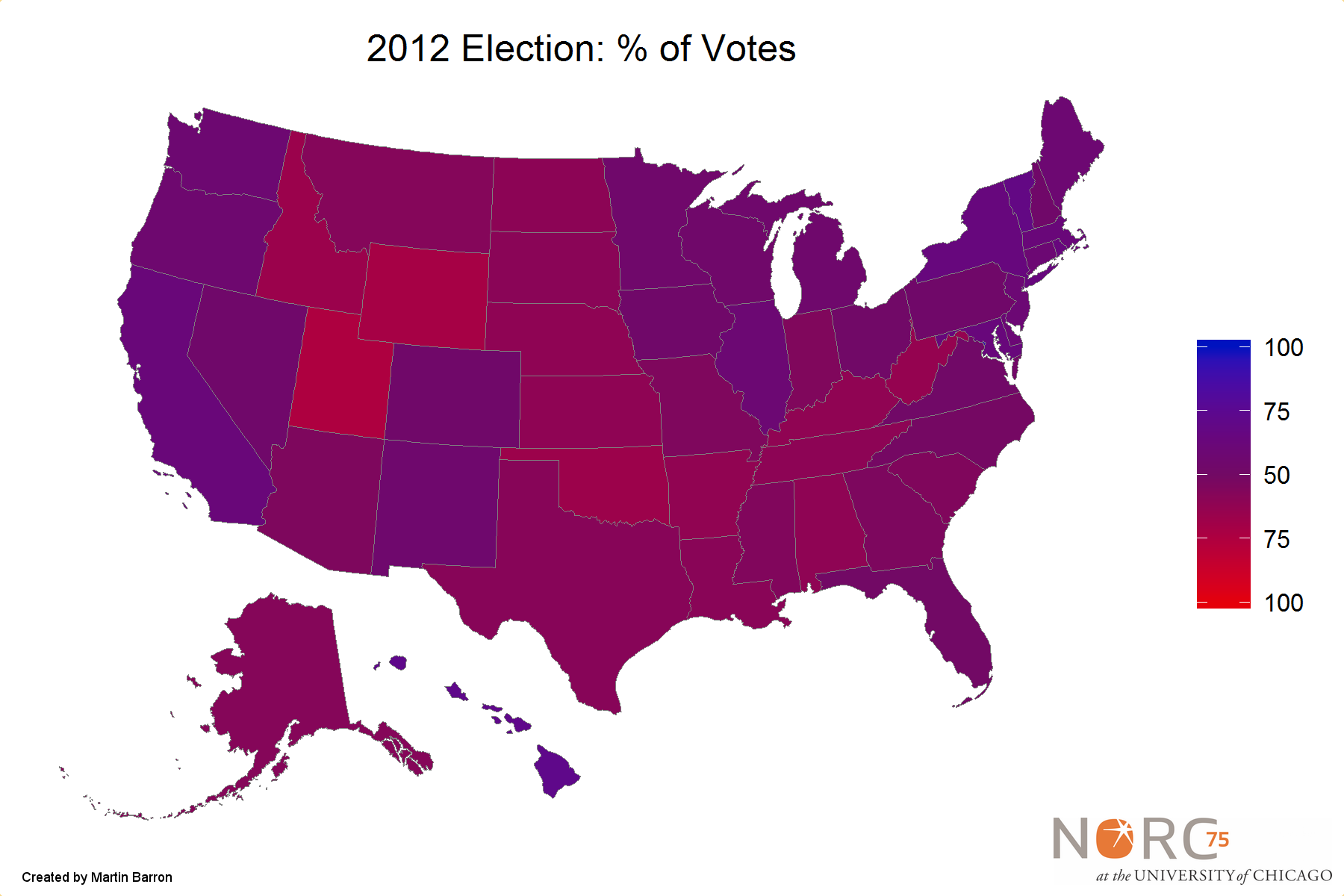

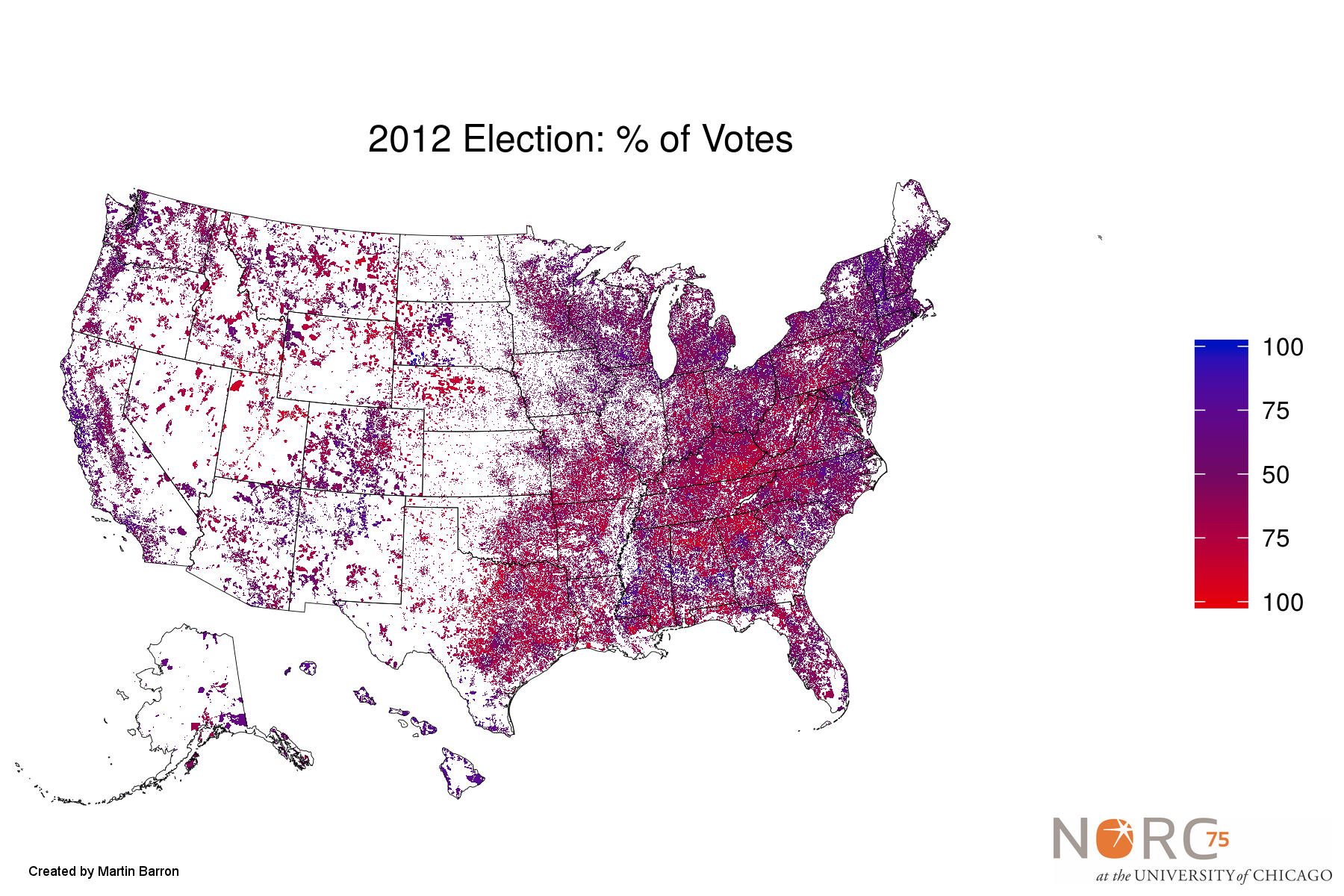

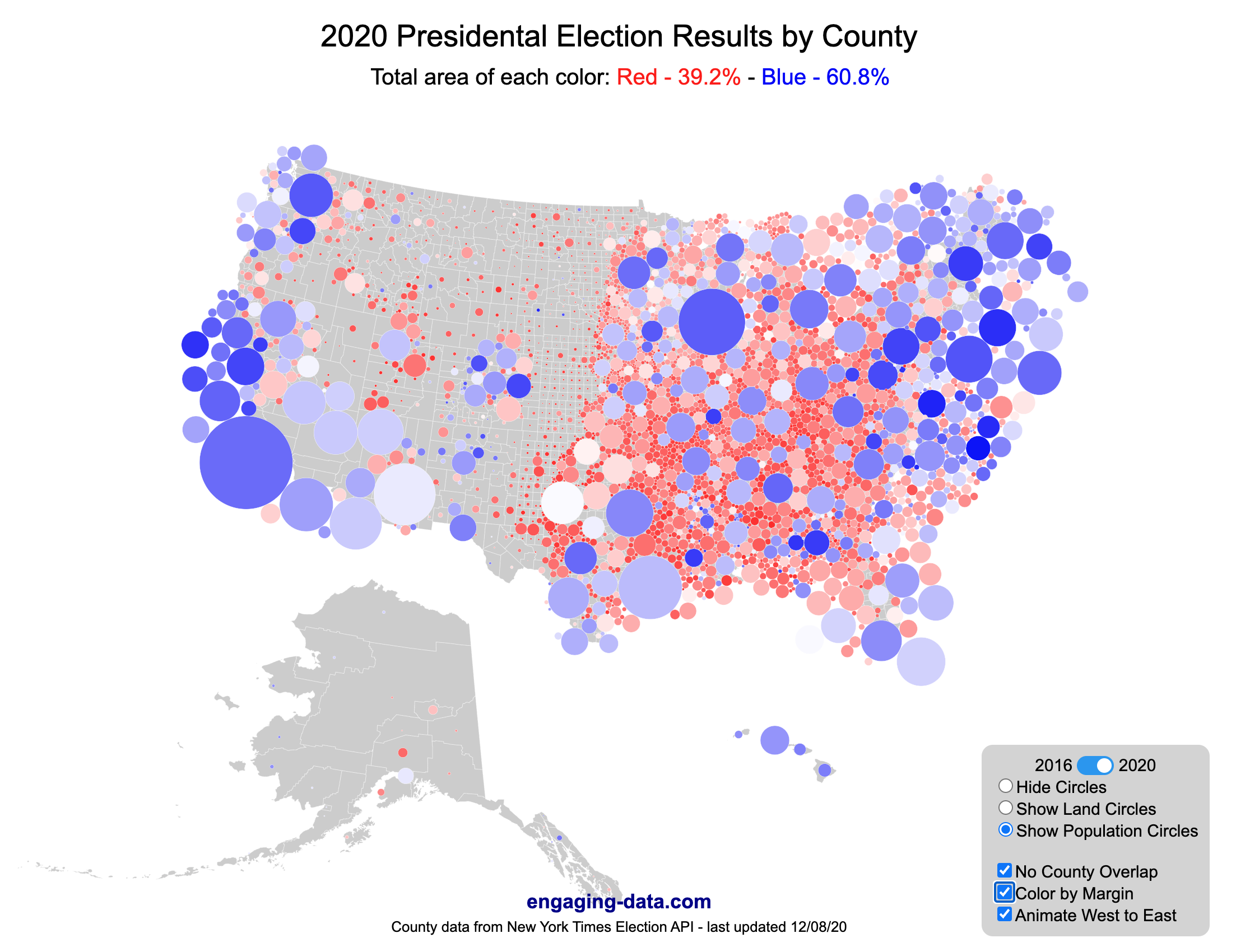

Maps representing various approaches to visualizing Republican/Democratic electoral support by state and by county.

Cultural Division In The US Today

I’ve spent seven years traveling around talking to people about faith and politics, and everywhere I go, and every online class I teach, I ask people a question about their home town. I ask what kinds of things divide people in that town from one another? What kinds of things become cultural boundaries that are difficult to cross?

And I got the idea for these questions from a talk by Jamie Smith, who’s written a fair share of books that are pretty influential in the reformed evangelical space.

But when it comes to asking people about their cultural boundaries, some of the answers are different person-to-person and place-to-place. But some answers come up over and over again: Education level. Owners vs. Renters. Townies vs. Transplants. Race and ethnicity. Income level and social class.

If our church looks like a Christian social club for white-collar people? If it looks like a safe space where white people don’t have to worry about saying the wrong thing for a couple hours a week? If it looks like a faith-based caucus within the Republican Party or the Democratic Party? We’re not demonstrating the power of the Holy Spirit to create a new people when we gather.

The church is called to be a community that draws together people of every tribe and tongue, even the tribes we dislike, and even the tongues we don’t speak. Our churches need to be places where the kinds of people who are likely to be Republican and the kinds of people who are likely to be Democrat and the kinds of people who are likely to feel left out of the process or left behind by the process or trampled over by the process can be seen coming together and not just tolerating one another, but actually trusting one another with their health, their safety, and their personal growth. Looking out for one another the way one body part looks out for the needs of another.

How Is Your Church Doing?

Is that what your church looks like now? Is that the kind of church you’d even be comfortable in at the moment? Let me know in the comments, and let me know what you think it would take to get there.

Building this kind of community wasn’t something the first Christians were equipped to do on their own. But it was something they were empowered to do through the support of the Holy Spirit, and for as grim as things look right now—and believe me, however grim you think it is, I’ve been there the last few years, too—but no matter how grim it looks right now, that kind of community is something that Christians in the US can start building toward together today.

If you want to work on how, then subscribe to our newsletter. We have more videos coming up on how partisan diversity happens in the church, how to foster it, and how to navigate it in a constructive way. If you’re signed up for our newsletter, then we’ll send you alerts about those videos as they come out, along with additional resources related to each one, and you’ll be the first to know when we roll out new tools and discussion guides.

Thank you for watching. Thank you for being part of this small community working to help the church think, speak and act differently in the public square, and I’ll see you next week.

Identify Your Culture's Boundaries

Take some time to write down or discuss the answers to the following questions:- Where do you currently live?

- What are some things that most people in that town have in common? What would you expect to be able to talk about with anyone from that town?

- What are some things that keep people in that town apart from one another? What are some of the barriers that people in your town don't usually cross when they socialize?